Mike Tyson revisited his old jail cell after 31 years — and left behind one item taped to the wall that shook the prison staff.

Tyson was given permission to visit the same Rikers Island cell where he once served time. Before leaving, he taped a laminated photo to the wall:

It was his first mugshot — with the words: “This man died here. I walked out new.” 🚔🖼️🚪

The Mugshot on the Wall

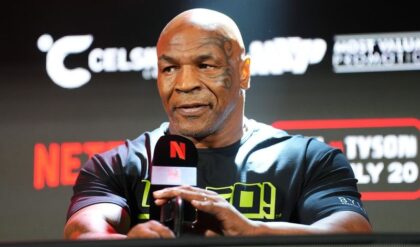

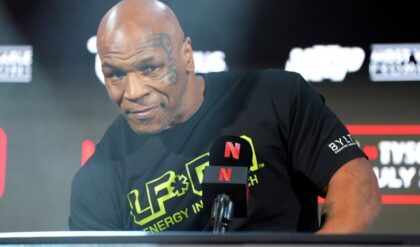

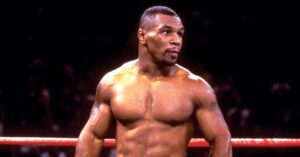

Thirty-one years had passed since Mike Tyson last set foot in the cold, gray confines of Rikers Island. Once the world’s most ferocious boxer, he was now a man in his late 50s, his face etched with the scars of battles fought both in and out of the ring. In 1992, he had served three years in this very prison, a chapter that nearly broke him. But on a crisp autumn morning in 2025, Tyson returned—not as a prisoner, but as a visitor, granted special permission to see the cell that had once held him captive. What he left behind would ripple through the prison, shaking the staff and inmates alike.

The journey to Rikers was quiet. Tyson sat in the back of a black SUV, staring out at the East River, his hands clasped tightly. His manager, Carla, had arranged the visit after Tyson confided in her about a recurring dream: the cell, the bars, the silence. “I need to go back,” he’d told her. “Not to dwell, but to close the door.” Carla, knowing the weight of his past, made it happen. The prison warden, intrigued by the request, agreed, though he warned that the facility had changed little since the ‘90s.

At Rikers, Tyson was escorted through security, his presence drawing whispers from guards and inmates. He wore a simple black hoodie and jeans, his once-intimidating frame softened by time. The warden led him down a narrow corridor, the air heavy with the clang of metal doors and the faint hum of fluorescent lights. When they reached Cell 214, Tyson paused. The door was ajar, the cell empty, its walls chipped and faded. “This is it,” he said softly, stepping inside.

The space was smaller than he remembered—barely enough room for a bunk, a sink, and a toilet. The memories flooded back: the sleepless nights, the rage that burned in his chest, the shame of a champion brought low. At 25, he’d been the youngest heavyweight champion, a force of nature. But in that cell, he was just another number, stripped of titles and glory. “I was angry at the world back then,” he told the warden. “But mostly, I was angry at myself.”

The warden, a stern man named Harris, nodded. He’d seen countless inmates come and go, but Tyson’s return felt different. “What made you come back?” he asked. Tyson ran a hand over the bunk’s cold frame. “To make peace,” he said. “And to leave something for the next guy who ends up here.”

For an hour, Tyson sat in the cell, alone with his thoughts. The guards kept their distance, sensing the weight of the moment. When he emerged, he carried a small plastic bag. Inside was a laminated photo, which he carefully taped to the wall above the bunk. The warden squinted at it: a black-and-white mugshot of a young Tyson, taken the day he arrived at Rikers in 1992. His eyes in the photo were defiant, his jaw set. Scrawled across the bottom in bold marker were the words: “This man died here. I walked out new.”

Tyson didn’t explain the photo. He simply shook the warden’s hand and left, the SUV carrying him back to the city. But the image lingered in Cell 214, a quiet testament that sparked a chain reaction no one could have predicted.

The first to notice was Officer Ramirez, a young guard assigned to the block. During his rounds, he spotted the photo and froze. He’d grown up watching Tyson’s fights on grainy VHS tapes, idolizing the champ’s raw power. But the words on the mugshot hit him harder than any punch. “This man died here.” Ramirez, who often felt hardened by the job, found himself rereading the note, wondering what it meant to die and walk out new.

Word spread among the staff. By the next shift, guards were stopping by Cell 214 to see the photo for themselves. Some dismissed it as a publicity stunt, but others felt its weight. Officer Jenkins, a 20-year veteran, stared at the mugshot and thought of the inmates he’d seen cycle through—men who never seemed to change. “Maybe Tyson’s saying you can,” he muttered to Ramirez. “Maybe you can leave the old you behind.”

The photo’s impact didn’t stop with the staff. Cell 214 was soon assigned to a new inmate, a 19-year-old named Darius, locked up for a robbery gone wrong. Darius was all bravado, his fists clenched, ready to fight anyone who looked at him sideways. But on his first night, he noticed the photo above his bunk. He read the words aloud, his voice echoing in the empty cell. “This man died here. I walked out new.” Something about it unnerved him. Tyson, the baddest man on the planet, had been in this same cell—and he’d changed.

Darius didn’t sleep much that night. He kept staring at the mugshot, thinking about his own path—gangs, bad choices, a mother who’d stopped visiting. The next day, he asked Ramirez about it. “Tyson left that himself,” Ramirez said. “Guess he wanted someone to know you don’t have to stay who you were.”

Over the weeks, Darius began to shift. He signed up for a GED program, something he’d scoffed at before. He started talking to the prison chaplain, asking questions about redemption. The photo became his anchor, a reminder that even a man like Tyson had found a way to start over. When other inmates noticed Darius’s change, they asked about the photo. Soon, Cell 214 became a quiet pilgrimage site, inmates and guards alike pausing to read the words taped to the wall.

The story reached the warden’s desk. Harris, moved by the unexpected impact, contacted Tyson’s team to thank him. In a phone call, Tyson’s voice was thick with emotion. “I didn’t know if anyone would care,” he admitted. “I just wanted to leave a piece of me behind—a piece that says you can rise, even from a place like that.”

Inspired by the photo’s effect, Harris launched a program called “New Paths,” inviting former inmates to share their stories with current ones. The first guest was Tyson himself, who returned to Rikers six months later. In the prison gym, he spoke to a packed room of inmates, guards, and staff. “That cell was my lowest point,” he said, his eyes scanning the crowd. “But it’s where I started to find myself. Whoever you are in here, that don’t have to be who you are forever.”

Darius, now months into his GED studies, sat in the front row, clutching a notebook. After the talk, he approached Tyson, showing him a poem he’d written about the mugshot. Tyson read it silently, then pulled Darius into a hug. “Keep walking out new, kid,” he said.

The laminated photo remained in Cell 214, untouched by time or turnover. It became a legend at Rikers, a symbol that even in the darkest places, transformation was possible. For the staff, it was a reminder of their role in that change. For the inmates, it was hope. And for Tyson, it was closure—a way to honor the man who died in that cell and celebrate the one who walked out new.