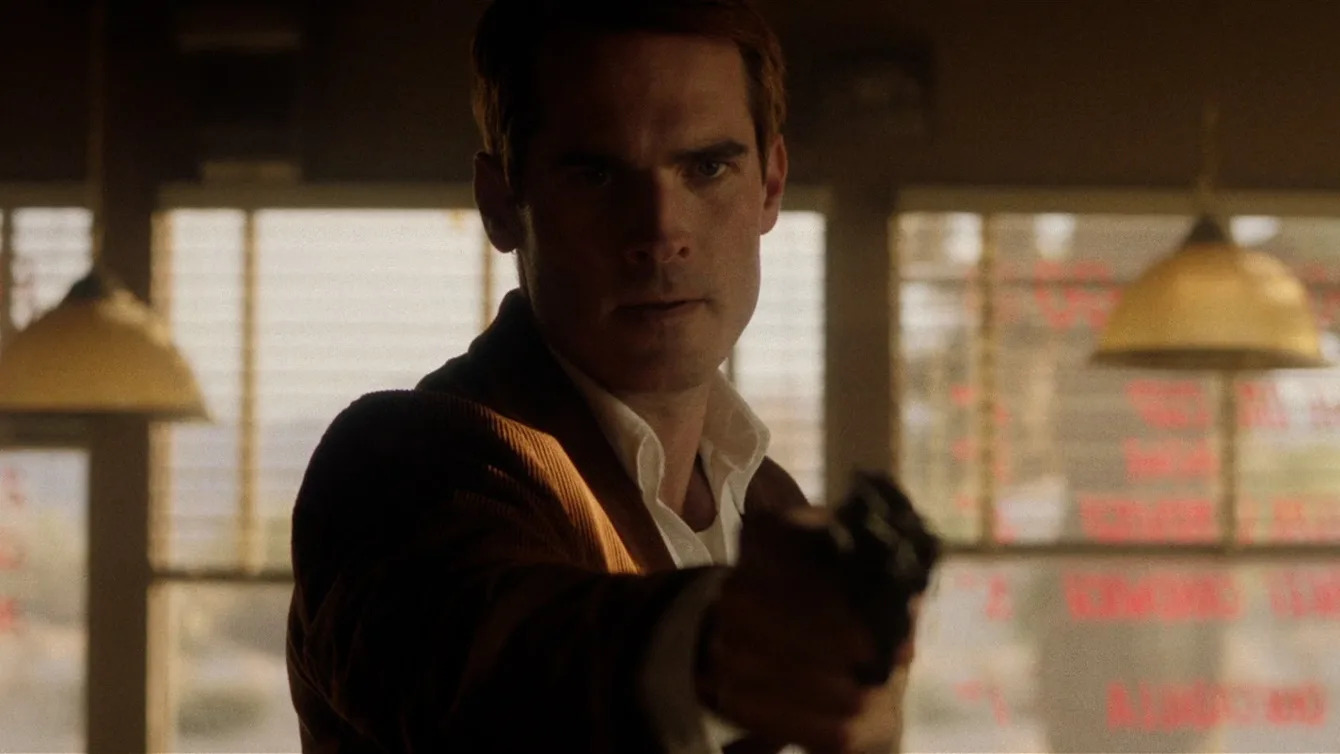

With his debut feature, “The Last Stop in Yuma County,” hitting theaters this week, Francis Galluppi is riding high. The Western-tinged neo-noir stars Jim Cummings as a nameless traveling knife salesman who finds himself in a unique position after witnessing a diner robbery while carrying a case of his sharp wares. The film charmed audiences on the genre festival circuit last fall and established Galluppi as a director worth watching. But as he nears the end of a five-year journey, the director hasn’t lost sight of how difficult it was to get his first project off the ground.

“I had two children in the time it took me to make this movie,” Galluppi said during a recent Zoom conversation with IndieWire. “My daughter’s first words were ‘The Last Stop in Yuma County.’”

Originally a musician by trade, Galluppi says that he originally felt compelled to pursue filmmaking after spending countless hours watching Hitchcock and Fellini movies in the back of his tour van. But he almost watched his directing career vanish before it truly began after a negative experience traveling to Cincinnati to debut his first microbudget short at a small festival.

“It was a terrible screening; nobody showed up,” Galluppi recalled. “It was an 8 a.m. screening the morning after the opening night party. And I flew out there at a time when I really had no money, and I was like, ‘Goddamnit, that was a waste of time.”

But the disappointing premiere led to a serendipitous meeting with James Claeys, a friend in the fashion industry who saw the artistic potential in Galluppi’s early work. Claeys offered the young director $50,000 with no strings attached to develop his next project. Sensing an opportunity to make his first feature, Galluppi began brainstorming ideas about an eclectic cast of vagabonds stranded at a gas station diner waiting for a fuel truck that eventually became “The Last Stop in Yuma County.”

Galluppi initially planned to make the movie on a $50,000 budget, but his script quickly attracted the attention of bigger investors. But as the prospect of a much larger budget flashed before his eyes, he began to realize that those resources would only come if he compromised on key aspects of the film, such as his insistence on casting Cummings as The Knife Salesman.

“I ended up optioning the script to this company that said, ‘We’re gonna make this for $5 million.’ And I was like, ‘Oh my god, this is crazy!’ And very quickly realized that it was the name game. You get this person with this much value, and that warrants a $5 million budget. And if you can’t get this person, you have no movie. It was just like, that wasn’t the movie I had in mind,” he said. “So once the option expired with that company, I just decided ‘I’m gonna go make this movie myself with whatever we have.’”

Back to square one and jaded by the development process, Galluppi turned his attention to plotting out his dream version of “Yuma County” without regard for his lack of funds. He eventually settled on a vision for the film that could be made for roughly $1 million and began assembling a cast and crew.

“I just started trying to pretend like we had money. I started shotlisting and photoboarding and writing letters to all these actors, hiring heads of departments and getting producers on board,” he said. “Basically, everything you can do without any money.”

It wasn’t long before the film was ready to shoot, but Galluppi still didn’t have a way to pay for it. He turned back to Claeys, whose $50,000 gift had set the entire film in motion. By this point, Claeys was so invested in the project in motion that he sold his house to finance the rest of it — granting Galluppi a level of creative freedom that few first-time directors ever enjoy.

“I get to the point where I have my dream cast, everything is shot-listed and ready to go, and we have no money. So James, the guy who put in the development money, ended up selling his house to finance it,” he said. “True story, he had been joking around with me like, ‘Hey, what if I just sold my house?’ I’m like, ‘That’s crazy, don’t fucking do that.’ Then, one morning, I just called him like, ‘Hey, I don’t know if you’re serious or not, but if you are, this is what it means. There’s gonna be nobody on set telling us what to do. We can do the movie that’s on the page.’ And he sold his house, and we were up and running a month later. It was as independent as it gets. Nobody was there for a paycheck, everyone was there for the right reasons because they believed in the project.”

In many ways, Galluppi achieved the dream that so many indie filmmakers spend their lives chasing — creative control on his debut feature, followed by a buzzy festival run that led to a theatrical release. Now that he’s had a chance to look back on that dream from the other side, Galluppi says he’s aware that it comes with more tradeoffs than most people expect. But he also acknowledged that for a true cinephile, the thrills of independent filmmaking are enough to justify the toll it takes on one’s lifestyle.

“I remember telling my wife ‘You realize this is my life, right? I’m going to write movies that nobody wants to make. I’m gonna struggle to find money, it’s going to take years off my life, and we’re probably not gonna make money off it,” he said. “Making an independent movie takes a long time. But if you love it, you don’t have a choice.”