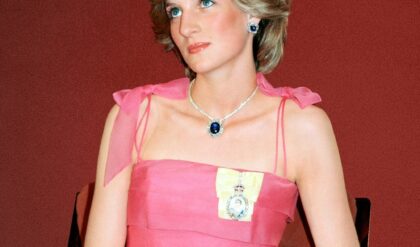

The viral claim echoing through online discussions: THE 36-MINUTE DELAY — The crash happened at 12:23 AM. Princess Diana reached Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital at 1:06 AM. Dr. Frédéric Mailliez, first on scene, later said, “She was alive when I leaned in.” Critics still question why nearly 40 minutes passed before transport

This timeline snippet highlights one of the most scrutinized aspects of the tragic events of August 31, 1997: the time between the crash in Paris’s Pont de l’Alma tunnel and Princess Diana’s arrival at the hospital. While the exact figures vary slightly across sources (crash at approximately 00:23–00:25 CEST, hospital arrival at 02:06), the core question persists—why did it take so long to get her to Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, roughly 4 miles (6.4 km) away? The delay, often cited as around 1 hour 40 minutes total from crash to arrival (with transport itself taking about 25–40 minutes), has fueled endless debate, speculation, and conspiracy theories.

However, official investigations—including the French judicial inquiry (1999) and the British Operation Paget report (2006)—concluded the delay stemmed from standard French emergency medical protocols at the time, combined with the severity of her internal injuries, rather than any deliberate foul play.

The Timeline: Key Moments

00:23 CEST — The Mercedes crashes into the 13th pillar in the Pont de l’Alma tunnel. Henri Paul and Dodi Fayed die instantly; Diana and bodyguard Trevor Rees-Jones survive initially.

Immediately after — Off-duty French doctor Dr. Frédéric Mailliez arrives (he was driving nearby), assesses the scene, and begins first aid. He later recounted: Diana was “alive,” “moaning,” “breathing but really weak,” “almost unconscious,” and struggling to breathe. He provided oxygen and noted no visible external injuries on her face, but she was in severe condition.

00:25–00:40 — Emergency services (SAMU, firefighters, police) arrive. Diana is extricated from the wreckage.

01:00 — Diana suffers a cardiac arrest at the scene; she is resuscitated.

01:18 — She is moved into the ambulance.

01:41 — The ambulance departs the scene (after prolonged on-site stabilization).

02:06 — Arrival at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital (journey takes ~25 minutes at 40–50 km/h).

02:10 onward — Cardiac arrest again en route/near hospital; doctors perform emergency surgery (including thoracotomy to repair a torn left pulmonary vein), but she is pronounced dead at 04:00.

The “36–40 minute” window often referenced refers to the time from initial stabilization efforts to departure (~01:00–01:41), or variations in reported times.

(Image: Archival photo of emergency services at the Pont de l’Alma tunnel shortly after the crash – emergency vehicles and personnel surrounding the wrecked Mercedes)

Why the Delay? French “Stay and Play” Protocol

France’s pre-hospital emergency system in 1997 (and still largely today) followed a “stay and play” approach, unlike the U.S./U.K. “scoop and run” model that prioritizes rapid transport to a hospital. French SAMU ambulances are mobile intensive care units staffed by doctors who stabilize patients on-site and en route before heading to a specialized facility.

Onboard doctor Jean-Marc Martino treated Diana for nearly 40 minutes at the scene to stabilize her breathing, blood pressure, and cardiac issues before deeming transport safe.

The ambulance drove slowly (25–31 mph / 40–50 km/h) with police escort to avoid jolting her fragile condition—sudden movements could worsen internal bleeding.

Near the hospital, her blood pressure dropped again; the ambulance stopped briefly for adrenaline and resuscitation.

Ambulance driver Michel Massebeuf later testified (2007 inquest): The doctor instructed slow driving due to her condition; they had police escort for smooth passage without stops.

This protocol was standard for severe trauma cases, especially internal injuries like Diana’s torn pulmonary vein (a rare but fatal injury from high-impact deceleration). Critics, including some U.K./U.S. doctors, argued rapid transport might have allowed quicker surgery—potentially saving her if she reached hospital sooner. However, experts noted her injury was likely unsurvivable long-term due to massive internal hemorrhage; time was critical, but the French approach aimed to prevent further deterioration en route.

Dr. Frédéric Mailliez’s Account

The off-duty doctor who first intervened emphasized Diana was alive and fighting when he reached her. In interviews (including 25th anniversary reflections in 2022), he described her as “very beautiful,” struggling to breathe, and in severe distress—but reacting. He administered oxygen from his emergency bag and called for help, unaware of her identity until the next day. He expressed lasting emotional weight: “I feel a little bit responsible for her last moments,” but affirmed he did everything possible initially.

Conspiracy Claims vs. Official Conclusions

The prolonged on-site treatment and slow journey have long been cited in theories suggesting deliberate delay (e.g., to ensure death). Mohamed Al-Fayed and others claimed foul play. Operation Paget (2006) and the 2008 British inquest examined this exhaustively:

No evidence of intentional delay or conspiracy.

Treatment followed French guidelines.

Verdict: unlawful killing due to grossly negligent driving by Henri Paul (intoxicated, high speed) and paparazzi pursuit—not murder.

Some medical hindsight suggested faster transport might have helped, but no proof the protocol caused preventable death—her injuries were catastrophic.

Nearly 30 years later, the “delay” remains a painful focal point of grief and scrutiny. It underscores differences in global emergency systems and the tragedy’s enduring questions—yet official evidence points to protocol, not plot.

A heartbreaking chapter where every minute mattered, but the outcome was sealed by the crash itself.