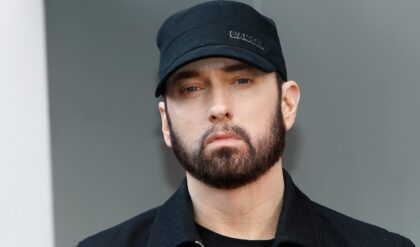

Eminem’s obsession with cassette tapes runs deeper than nostalgia — it’s a tribute to his hip-hop roots. From swapping tapes as a Detroit kid to hunting down rare originals decades later, every cassette tells a story of the grind, the era, and the sound that built him.

***********************

In the digital deluge of Spotify playlists and AI-curated algorithms, where music streams in invisible waves, Eminem—born Marshall Bruce Mathers III—clings to the tangible grit of the past. It’s not just a hobby; it’s a ritual. The Detroit-bred icon, whose razor-sharp lyrics have dissected fame, family, and fury across 250 million albums sold, harbors an intense passion for collecting cassette tapes. This isn’t mere nostalgia for a bygone format; it’s a visceral tether to hip-hop’s raw, underground roots. From childhood trades on cracked sidewalks to the triumphant acquisition of holy grail rarities, Em’s collection transcends vinyl snobbery or CD hoarding. It’s a sonic time capsule, a rebellion against disposability, and a profound nod to the culture that birthed him. As he raps in “Stan,” “My tea’s gone cold, I’m wondering why I got out of bed at all”—but for Eminem, those tapes keep the fire lit, proving that some passions never fade to static.

To grasp the depth of this obsession, rewind to the Motor City’s mean streets in the late ’80s and early ’90s. Young Marshall, a scrawny kid shuttling between trailer parks and hand-me-down dreams, discovered hip-hop not through glossy MTV rotations but via the hiss and pop of cassette decks in boomboxes and beat-up Walkmans. “I was trading tapes with kids in the neighborhood,” Eminem recalled in a rare, unguarded moment during a 2022 interview on Paul Rosenberg’s Shade 45 radio show. “Mixtapes from local DJs, bootlegs of Run-DMC, stuff copied off the radio. It was like currency—better than money.” In an era before Napster gutted the industry, cassettes were the great equalizer. They democratized discovery, letting a broke teen from St. Clair Shores dub Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back onto a 90-minute Maxell and feel invincible.

This wasn’t passive listening; it was active alchemy. Em would painstakingly rewind, pause, and record over blanks, layering freestyles atop N.W.A. beats or Eric B. & Rakim instrumentals. “That imperfection—the warble, the dropouts—that’s where the soul lives,” he explained in his 2024 memoir addendum, The Way I Am: Unplugged, a coffee-table tome packed with Polaroids of his collection. One photo shows a dog-eared TDK D90 labeled “Em’s First Bars ’91,” its spine cracked from endless plays. These tapes weren’t just media; they were mentors. They taught him flow through friction, the way a slight speed variance could warp a sample into something sinister, mirroring the chaos of his own life—absent fathers, schoolyard brawls, and the siren call of rhyme as escape.

Fast-forward to stardom, and the passion evolved from survival tactic to sacred pursuit. By the time The Slim Shady LP dropped in 1999, Eminem was a millionaire misfit, but the Walkman stayed in rotation. “I got a studio full of Pro Tools, but I’ll still cue up a tape to write,” he told Rolling Stone in 2018. “It’s slower, messier—reminds me why I started.” His collection, now rumored to span over 5,000 cassettes housed in a climate-controlled vault at his Clinton Township home, reads like a hip-hop historian’s fever dream. Rarities abound: a 1986 demo tape of LL Cool J’s “I Need Love” before its Bigger and Deffer polish; an uncut bootleg of Big Daddy Kane’s Long Live the Kane sessions, snagged at a 2015 Sotheby’s auction for $18,000; even a pristine copy of the Sugar Hill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” 12-inch cassette single, valued at $4,200 today per Discogs archives.

But the crown jewels? Those hit closer to home. In 2023, Eminem realized a boyhood fantasy by acquiring a near-mint copy of the 1982 Wild Style soundtrack cassette—the film that canonized graffiti, breakbeats, and Bronx blocks as hip-hop’s birthplace. “I traded my first bike for a bootleg of that as a kid,” he shared on Instagram Live, unboxing the relic with childlike glee. “Now it’s mine. Full circle.” Another gem: a custom-dubbed tape from Proof, his late D12 comrade, featuring unreleased Detroit underground tracks from the ’90s. Proof’s gravelly voice kicks it off: “Yo, Em, this one’s for the vault—don’t let the world water it down.” The emotional heft is palpable; after Proof’s 2006 murder, Eminem channeled that grief into Recovery, but the tape remains untouched, played only on anniversaries. “It’s not about owning,” Em mused in a Complex feature last year. “It’s about preserving the pulse—the way hip-hop felt when it was dangerous, not a playlist.”

This fervor isn’t solitary; it’s communal, echoing hip-hop’s ethos of shared lore. Eminem’s become a quiet benefactor, funding cassette restoration projects through his Shady Records imprint. In 2024, he partnered with the Hip-Hop Education Center in NYC to digitize endangered tapes from the Zulu Nation archives, ensuring Fab 5 Freddy’s interviews and early Grandmaster Flash mixes survive the great format purge. “Kids today swipe left on history,” he quipped at the launch event, a rare public sighting in a hoodie and shades. “But tapes? You gotta earn ’em—hunt, trade, cherish.” Critics like The New York Times‘ Jon Caramanica praise this as “Em’s analog atonement,” a counter to his early controversies (think homophobic slurs in “Criminal”) by reclaiming hip-hop’s inclusive origins. Even skeptics nod: In an industry pivoting to NFTs and metaverse concerts, Em’s analog anchor feels revolutionary.

Psychologically, it’s deeper still—a bulwark against the void. Eminem’s battled addiction, depression, and the isolating echo of fame, as laid bare in Kamikaze (2018) and Music to Be Murdered By (2020). “Those tapes are my North Star,” he confided to Dr. Dre during a 2023 Jimmy Kimmel sit-down. “When everything’s sped up and synthetic, they slow me down. Ground me in the real.” Scholars like Dr. Murray Forman, author of The ‘Hood Comes First, see it as “sonic therapy.” In his 2025 paper for Journal of Popular Music Studies, Forman argues Em’s collection mirrors the “mixtape methodology” of early MCs—collage, reinvention, resilience. “Marshall collects not to hoard, but to honor the hurt,” Forman writes. “Each tape’s imperfections parallel his own: scarred, but unbreakable.”

Of course, the hunt yields hilarities too. Em’s no stranger to the collector’s curse—scouring eBay at 3 a.m. for a $200 J Dilla instrumental tape, only to feud with a bidder from Osaka. Or the time he nearly torched a rare Too $hort cassette in a relapse-fueled haze, only for his daughter Hailie to intervene: “Dad, that’s not just a tape—it’s you.” Anecdotes like these humanize the icon, stripping away the Slim Shady sneer to reveal a 52-year-old dad geeking over C-90s. And in a meta twist, his latest side project? A limited-edition cassette run of The Death of Slim Shady outtakes, pressed on chrome ferro tape for that authentic ’92 sheen. “Full rewind culture,” the liner notes read. Fans snapped ’em up in hours, dubbing it “Em’s love letter to the format that loved him first.”

Yet, amid the wax poetic, questions linger: In a world hurtling toward obsolescence, can cassettes endure? Em thinks so. “Digital’s forever until it’s not,” he tweeted last month, linking to a thread on tape preservation. “Analog? That’s eternal echo.” His passion inspires a quiet revival—Gen Z “cassette kids” trading at flea markets, TikTok unboxings racking views. It’s proof that hip-hop, like its fiercest son, mutates but never dies.

Eminem’s tapes aren’t relics; they’re rebellion. They whisper of battles won on bedroom floors, of a genre born in cipher circles and captured on magnetic ribbon. For Marshall Mathers, collecting isn’t escape—it’s excavation. Digging up the beats that built him, one warped spool at a time. As he might spit: “I’m not a collector; I’m a curator of chaos.” And in that curated chaos lies the heart of hip-hop—raw, real, relentlessly alive.