Penelope Featherington changes her wardrobe, drawing inspiration from Marilyn Monroe; Eloise Bridgerton’s dresses remind us of Audrey Hepburn’s style;and Cressida Cowper’s extravagant dresses improve the young lady’s chances to find a husband this season

Should drama series and films serve as a history lesson and present an accurate picture of the era they depict? It depends on who you ask. Costume designers are taking liberties by interpreting contemporary fashion. Famous examples include the 2006 film “Marie Antoinette,” featuring hidden Converse sneakers, or the Victorian costume in “Poor Things.”

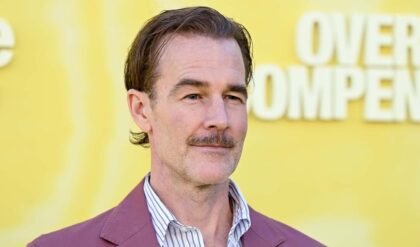

The “Bridgerton” drama, now in its third season on Netflix, takes viewers on a journey that deviates from the historical accuracy of the series’ plot set in the 19th century. While the velvet and silk are era-appropriate, the designs are not. Costume designer John Glaser explained in interviews that, unlike the previous two seasons, this time he had more freedom in character design, with less historical scrutiny.Glaser moves forward and backward in fashion history, with Queen Charlotte’s grandiose hairpieces from the late 18th-century, playing with changing silhouettes of 19th-century dresses, and drawing inspiration from two major stars of the 20th century: Audrey Hepburn and Marilyn Monroe.

One of the beautiful examples of transitioning between eras can be seen in the character of Eloise Bridgerton interacting with Audrey Hepburn. The white ball gown worn by Eliza Doolittle in the 1964 film “My Fair Lady” (set in the early 20th century) served as inspiration for Eloise’s bejeweled ball gown. In another instance, she wears a silk sapphire dress, which is similar to a garment worn by Doolittle in the film. When asked about her wearing so much blue, Eloise replies that it’s the fashion of the season, indicating the season’s change.

Transformation of Penelope and Cressida

The focus on clothes as tools for identification and interpretation has been present since the beginning of the first season. The costume design department of the series created a color scheme for each of the main families in the series: yellow for the Featheringtons, blue for the Bridgertons. These boundaries allow, according to Glaser, “a sharpening of historical research alongside references to fashion and art – from abstract paintings to high fashion shows – to integrate and develop the personal costumes of each character.”

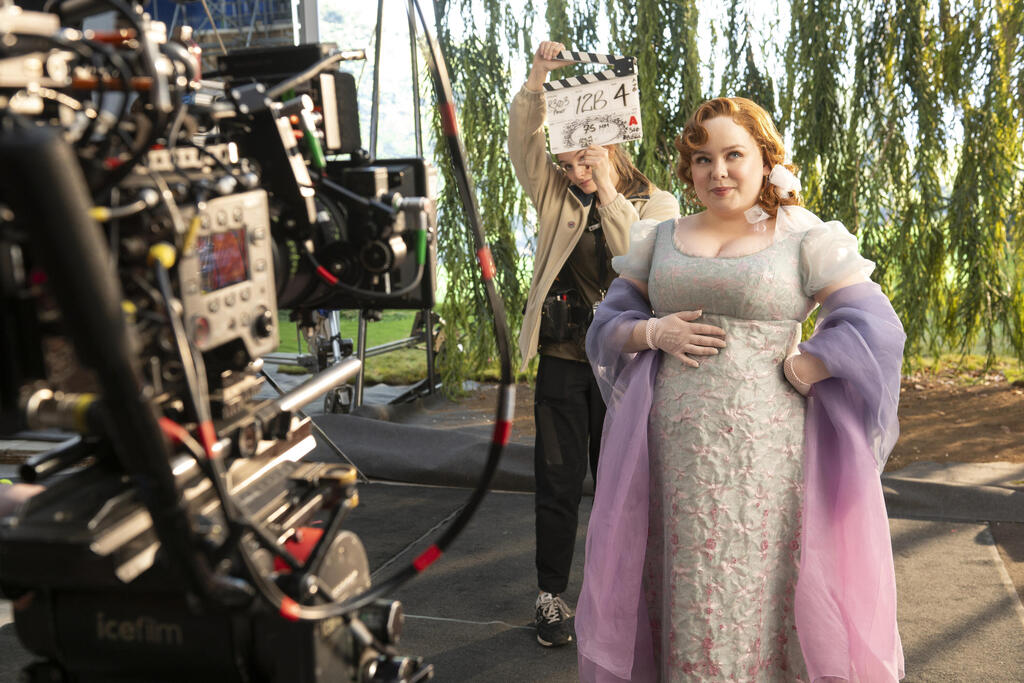

The character undergoing the most significant transformation this season is Penelope Featherington, portrayed by actress Nicola Coughlan, with a central theme of the season being her relationship with Colin Bridgerton portrayed by Luke Newton. She undergoes a transformation right before she re-enters society and tells her seamstress, Madame Delacroix, that she does not want to see citrus colors again. As a result, she distances herself from the yellows in favor of greens, like the evening gown which she wore to the grand ball.

The changing colors tell a bigger story. Penelope realizes that if she wants to get married she needs to change. She decides to transition from her family’s flowery and ornate garments to clothes in shades of green and blue associated with the Bridgerton family. These parallels also reflect the personal change she undergoes, attempting to look more appealing to society.

This transition shows the character’s development in the series, raising questions about the power of one’s choice of clothes in regard to personal expression and their influence on us, as well as critical questions like should a women change to get a husband.

Glaser explains how the change works. In an interview with InStyle, he describes Penelope’s entry as head-turning, unlike the previous seasons. “It’s the first time we see her new hair, which is a beautiful color of red. And in this dress, this fabric goes from green to rust to help with their hair. And that’s why this cloak is rust. So it just becomes one nice solid image.”

More than in previous seasons, the new season of “Bridgerton” focuses on highlighting Penelope’s body structure, rather than hiding it. Glaser did this by changing the silhouette of the 1820s dress to Marilyn Monroe’s Hollywood glamor of the 1950s.

Another prominent character this season is Cressida Cowper, who receives an array of extravagant costumes, such as luxurious evening gowns, some adorned with feathers and ruffles, creating a visual representation of a giant peacock. This is another way to distinguish a TV character’s personality development through clothes, conveying additional messages to viewers who choose to focus on the colorful style of the series, rather than the plot developments.